A member of the exclusive and very small club of noble fibre textile producers, Lanifício Luigi Colombo arrives in Portugal with its tailoring line.

If it’s true that the shape, or design if you prefer, of a garment is fundamental, it’s no less true that, for the more knowledgeable consumer, the origin and raw material used in its construction is no less important and can determine not only factors such as durability and the architecture of a garment, from its construction to its aesthetic appearance, but also more practical issues such as thermal efficiency or the more obvious price-quality ratio.

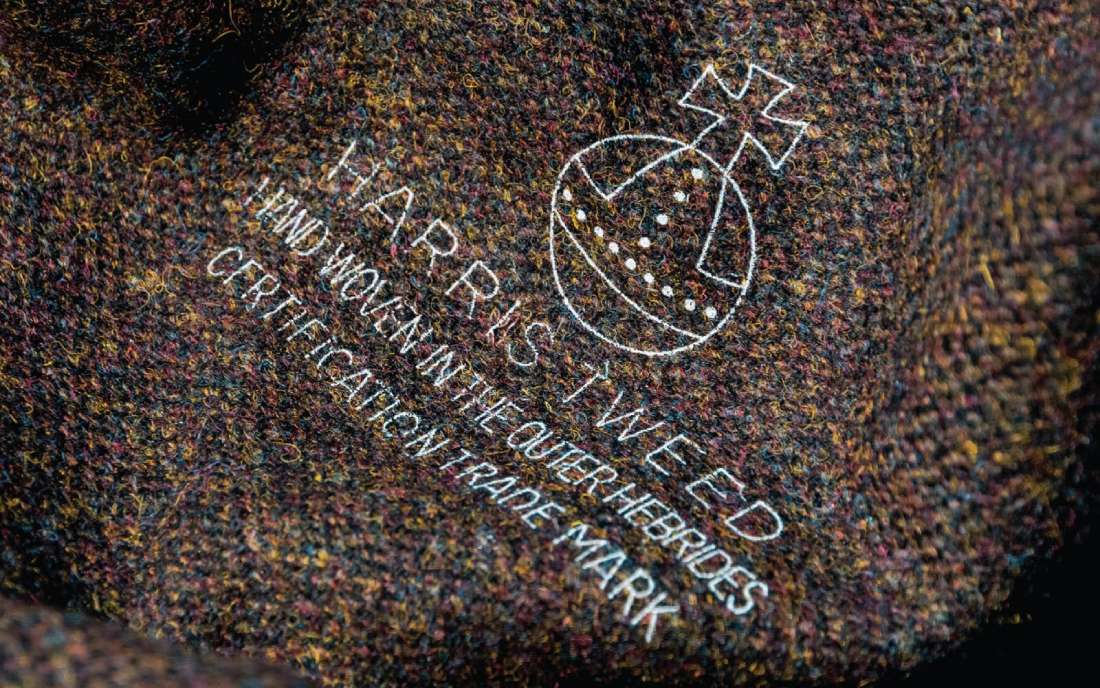

One of the advantages of tailoring over ready-to-wear is precisely that the customer has a say in choosing the material their garment will be made from. Apart from fleeting trends dictated by fashion, the customer can choose from a wide range of posters in which fibres, colours, textures, weights, origins, manufacturers and, of course, prices are presented in the form of fabric.

The exercise, which can be somewhat intimidating for neophytes, is a pleasure for connoisseurs who can let their imagination run wild in a game where there are few barriers other than one’s taste and, of course, the amount of money involved, which can make the game very expensive. What we have left is the consolation that when it’s right, madness can be seen as a long-term investment in pleasure.

As with everything in life, there are different levels here too, and as someone once said: “What’s expensive isn’t always good, but what’s good is inevitably expensive.”

The noble fibres club is at the forefront of this activity.

Of animal origin, it includes the hair of animals, goats, sheep and other bovids and camelids originating in inhospitable regions of the planet such as Mongolia or the Andes in South America, from whose fur, or wool, some of the most protective, beautiful and precious fabrics the world has ever seen are made.

Due to its rarity, delicacy and demanding treatment and consequent cost, there are very few houses dedicated to processing this exquisite raw material and even fewer that successfully work with it at the highest level, making it the luxury raw material that it is, by all definitions.

In this highly prestigious niche industry, where Made in Italy is king and master and whose best-known name is Loro Piana, the world’s leading producer of noble fibres is Laníficio Luigi Colombo.

So when you buy cashmere or any other noble fibre such as vicuña, guanaco, camel’s hair or merino wool in tailoring fabric or already transformed into clothing from a luxury brand, even though the manufacturer’s name is usually not on the label, if you are really looking at a fabric of undeniable quality, there is a strong probability that it was produced by Lanifício Luigi Colombo.

The family textile company was founded by Luigi Colombo. Born in 1927 in Tradate in Lombardy into a family linked to industry, he was orphaned at the age of 10 and raised by his uncle, a prestigious textile entrepreneur from Biella in the neighbouring region of Piedmont. Regarded as a sensitive and highly intelligent man with a very strict work ethic, by the age of 20 he was already in charge of his uncle’s factory.

After getting married, Luigi decided to go into business for himself in the noble fibres sector, an activity in keeping with his creative and adventurous spirit.

In the 1970s, sons Roberto and Giancarlo joined their father, injecting a dose of youth and audacity that would be decisive for the company’s future. In addition to establishing direct relationships with wool suppliers around the world, from the Andes to Australia to China, where they began to negotiate directly with Mongolian shepherds.

This attitude has allowed them to establish privileged contact with shepherds and breeders, and to better control the product at source. At the same time, a strong and continuous policy of investment in research and innovation has given them an enviable position in the market.

By the 1980s they had the main names in international fashion as their clients. With the luxury industry growing and the demand for high quality fabrics increasing, they became leaders in the noble fibres sector, becoming specialists in cashmere, guanaco, vicuña, camel, and fibres from well-known species such as mink, chinchilla or sable, but which are not commonly used as textiles, not least because of their price.

The company, which is now in its third generation, currently has two factories, in Borgosesia and Ghemme, covering an area of 30,000 square metres, where around 400 people work and process more than 500,000 kilos of raw materials a year.

The highly specialised workforce, where experience and manual labour alternate with the most advanced spinning technology, is one of the great assets of this family-run business that wants to continue to grow in a sustained manner.

As well as supplying the world’s most famous fashion houses, Lanifício Colombo launched its own pret-a-porter line in the mid-1980s, with knitwear, accessories and home textiles in multi-brand outlets, prestigious department stores and its own shops. Its shops in Italy can be found in Milan on the famous Via della Spiga, Via Borgognona in Rome, Bergamo and Porto Cervo and, outside Italy, in South Korea in Seoul, Daegu and Busan.

The arrival in Portugal, where it is now available in the capital in a fabric by the metre at Sumisura, opposite the Ritz Four Seasons, is part of an expansion plan to take the Laníficio Colombo name to new markets. The strategy, according to those responsible for the brand, also involves opening new

shops although Lisbon, at least for now, is not being considered.

Fernando Pereira, a specialist in Made to Measure tailoring who already offers the most important names in the tailoring fabric market, Laníficio Colombo’s noble fibres further enhance Sumisura’s offer, whose customers can now touch and feel what is probably the best cashmere in the world.